James Watt: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

<b>The Watt engine</b> | <b>The Watt engine</b> | ||

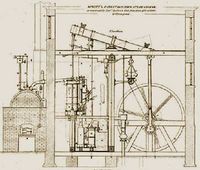

[[File:Watt.jpg|200px|thumb]] | [[File:Watt.jpg|200px|thumb|left|The Steam Engine]] | ||

While fixing a prototype Newcomen steam engine in 1764, Watt was struck by its inefficient use of steam. In May 1765, following efforts to tackle its improvement, he discovered a solution—the separate condenser, his first and most noteworthy invention. Watt recognized that the Newcomen engine's major flaw was the loss of latent heat (heat involved in changing a substance's state, such as from solid to liquid). Thus, he concluded that condensation needed to occur in a separate chamber connected to, but distinct from, the cylinder. | While fixing a prototype Newcomen steam engine in 1764, Watt was struck by its inefficient use of steam. In May 1765, following efforts to tackle its improvement, he discovered a solution—the separate condenser, his first and most noteworthy invention. Watt recognized that the Newcomen engine's major flaw was the loss of latent heat (heat involved in changing a substance's state, such as from solid to liquid). Thus, he concluded that condensation needed to occur in a separate chamber connected to, but distinct from, the cylinder. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

<b>Legacy</b> | <b>Legacy</b> | ||

[[File:James-watt2 statue.jpg|200px|thumb|right|The Statue of James Watt Glasgow, Scotland.]] | [[File:James-watt2 statue.jpg|200px|thumb|right|The Statue of James Watt in Glasgow, Scotland.]] | ||

The Watt engine played a crucial role in shaping the Industrial Revolution by quickly integrating into numerous industries. Due to Watt's advancements in science and industry, the watt, a unit of power in the International System of Units (SI), representing one joule of work performed per second (or 1/746 horsepower), was named in his honor. | The Watt engine played a crucial role in shaping the Industrial Revolution by quickly integrating into numerous industries. Due to Watt's advancements in science and industry, the watt, a unit of power in the International System of Units (SI), representing one joule of work performed per second (or 1/746 horsepower), was named in his honor. | ||

Revision as of 17:00, 7 January 2024

1736-1819. Scottish inventor, famous for improving Thomas Newcomen's steam engine.

James Watt (born January 19, 1736, Greenock, Renfrewshire, Scotland—died August 25, 1819, Heathfield Hall, near Birmingham, Warwick, England) was a Scottish instrument maker and inventor whose steam engine played a significant role in shaping the Industrial Revolution. Watt gained recognition for patenting both the double-acting engine and an early steam locomotive. In 1785, he achieved the honor of being elected as a fellow of the Royal Society of London.

Education and training

Watt's father managed a successful ship- and house-building enterprise. Watt received early education from his mother at home and later, during his time in grammar school, he acquired knowledge in Latin, Greek, and mathematics. A crucial part of his learning came from his father's workshops, where he used his own tools, workbench, and forge to create models (e.g., cranes and barrel organs) and became acquainted with ship instruments.

At the age of 17, Watt decided to pursue a career as a mathematical-instrument maker. He initially traveled to Glasgow and in 1755 to London, where he found a master to guide his training. Though health problems prevented him from completing a proper apprenticeship, by 1756 he felt he had acquired sufficient skill “to work as well as most journeymen.” Upon returning to Glasgow, Watt opened a shop in 1757 on the university campus, specializing in the production of mathematical instruments such as quadrants, compasses, and scales.

During his time at the university, he formed connections with many scholars and scientists. Among them were renowned economist Adam Smith and British chemist and physicist Joseph Black, whose experiments on the concept of latent heat would prove crucial to the development of Watt's future steam engine designs. In 1764, Watt married his cousin Margaret Miller, and over the next nine years, they had six children before her untimely death. In 1777, Watt married Ann MacGregor, daughter of a Glasgow dye-maker and the couple had two children.

The Watt engine

While fixing a prototype Newcomen steam engine in 1764, Watt was struck by its inefficient use of steam. In May 1765, following efforts to tackle its improvement, he discovered a solution—the separate condenser, his first and most noteworthy invention. Watt recognized that the Newcomen engine's major flaw was the loss of latent heat (heat involved in changing a substance's state, such as from solid to liquid). Thus, he concluded that condensation needed to occur in a separate chamber connected to, but distinct from, the cylinder.

Soon after, he met John Roebuck, a British physician, chemist, and inventor, known for founding the Carron Works. Roebuck encouraged him to develop an engine. In 1768, they formed a partnership after Watt created a small test engine with financial support from Joseph Black. The next year, Watt secured the renowned patent for "A New Invented Method of Lessening the Consumption of Steam and Fuel in Fire Engines."

While working as a land surveyor in 1766, Watt remained consistently occupied for the next eight years, marking out canal routes in Scotland. Hence, this work obstructed his advancement with the steam engine. Following Roebuck's bankruptcy in 1772, Matthew Boulton, an English manufacturer and engineer associated with the Soho Works in Birmingham, acquired a share in Watt's patent. Disinterested in surveying and in Scotland, Watt relocated to Birmingham in 1774.

Following the extension of Watt's patent through an act of Parliament in 1775, he and Boulton initiated a 25-year partnership. Boulton's financial support facilitated rapid advancements with the engine. By 1776, two engines were put into operation—one for water pumping in a Staffordshire colliery, and the other for supplying air to the furnaces of British industrialist John Wilkinson, the renowned ironmaster.

Over the following five years, until 1781, Watt dedicated substantial time to the installation and supervision of numerous pumping engines for the copper and tin mines in Cornwall. Lacking business expertise, Watt had to endure tough negotiations to secure sufficient royalties for the new engines.

The next year, anticipating a fresh market in corn, malt, and cotton mills, Boulton encouraged Watt to create a rotary motion for the steam engine, replacing the original reciprocating action. In 1782, he secured a patent for the double-acting engine, where the piston both pushed and pulled. A new approach was required to firmly link the piston to the beam in this engine. In 1784, he addressed this issue by inventing the parallel motion, a system of interconnected rods that directed the piston rod in a perpendicular motion.

James Watt's later years

Demand for Watt's steam engine across various industries led to considerable wealth by 1790. In addition to his business success, Watt engaged in scientific pursuits, joining the Lunar Society and conducting experiments. Elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1785, he eventually took holidays, acquired an estate, and gradually withdrew from business after 1795.

During his extended retirement, marked by the loss of his son Gregory, his sister Margaret, and his daughter Jessy. Watt also mourned the loss of old friends, including Wedgwood in 1795, Black in 1799, Darwin in 1802, Priestley in 1803, and Robison in 1805. However, he was to experience an even more significant loss with the passing of his partner, Boulton. Nevertheless, Watt and his wife traveled to Scotland, France, and Germany after the Peace of Amiens in 1802.

In his old age, Watt feared his mental faculties might decline, so he resumed studying German and quickly regained proficiency. Watt maintained both his mental faculties and inventive powers until the end, demonstrated by his successful resolution of a problem posed by the Directors of the Glasgow Water Works in 1810. Watt's impressive inventive skills in his later years are also highlighted by his work on the sculpturing machine which he had set up in the attic of his house. In his workshop, he used the sculpturing machine to replicate original busts and figures for his friends.

Watt also served as a consultant to the Glasgow Water Company. His accomplishments were duly recognized, with honors including a doctorate of laws from the University of Glasgow in 1806 and a foreign associate position in the French Academy of Sciences in 1814 and a baronetcy, which he turned down.

Legacy

The Watt engine played a crucial role in shaping the Industrial Revolution by quickly integrating into numerous industries. Due to Watt's advancements in science and industry, the watt, a unit of power in the International System of Units (SI), representing one joule of work performed per second (or 1/746 horsepower), was named in his honor.

Certain scientists maintain that the introduction of the parallel motion (or double-acting engine) in 1784 marks the initiation of the Anthropocene Epoch—an unofficial period in geological time when human activities started to impact Earth's surface, atmosphere, and oceans significantly. After four years, he incorporated the centrifugal governor for the automatic regulation of the engine's speed, based on Boulton's recommendation, and in 1790, inventing a pressure gauge, he essentially finalized the Watt engine.

Demand for Watt's steam engine across various industries led to considerable wealth by 1790. In addition to his business success, Watt engaged in scientific pursuits, joining the Lunar Society and conducting experiments. Elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1785, he eventually took holidays, acquired an estate, and gradually withdrew from business after 1795.

Sources

- Kingsford, Peter W.. "James Watt". Encyclopedia Britannica, 14 Dec. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Watt.

- Dickinson HW. Life in retirement, 1800–1819. In: James Watt: Craftsman and Engineer. Cambridge Library Collection - Technology. Cambridge University Press; 2010:182-200.